The civil suits are largely on hold—thanks to a legally-debatable decision by Judge Beaty to delay discovery while Durham’s attorneys (who have, to date, billed the city for nearly $5 million, according to the AP) appeal to the 4th Circuit. Attorneys for the falsely accused players have now filed their response to the city’s legal theories.

Summarizing the Case

The Durham brief (filed in late July) summarizes events of the case in an almost comical form, as if what occurred was little more than a routine police investigation beset by no procedural improprieties: “Stripper[] Crystal Mangum alleged that she had been raped at that party. Durham police investigated her allegations—meeting with witnesses and working through the district attorney’s office to obtain DNA evidence. After ten days of investigation, State Prosecutor [sic: District Attorney] Michael Nifong became involved in the case. He was fully briefed by City investigators as to the available evidence. Nifong later sought, and obtained, indictments against Plaintiffs. Plaintiffs were briefly arrested following indictment, and then immediately released while the investigation continued. The charges and indictments were later dismissed.” Indeed, according to the Durham attorneys, the “factual allegations [in the case] do not give rise to a plausible inference of malice.”

And here’s how the Durham brief describes the no-fillers-allowed photo array: “On April 4, 2006, Sergeant Gottlieb showed Crystal Mangum additional photograph arrays of Duke lacrosse players,” who had, by this point, been publicly identified by Nifong and the DPD as suspects.

The falsely accused players’ response frames the context more appropriately: “The Complaint describes one of the most notorious episodes of police, prosecutorial, and scientific misconduct in modern American history. It details the sustained, coordinated actions of police and City officials to fabricate evidence, conceal evidence of Plaintiffs’ innocence, inflame the community with false public statements, and mislead the grand juries, resulting in the unlawful arrests of Plaintiffs without probable cause.”

Ignorance Is Bliss

In what attorneys for the falsely accused players correctly deem “the City Defendants’ ‘blame Nifong’ approach,” the Durham brief goes to considerable length to suggest that ex-DPD officers Mark Gottlieb and Ben Himan can’t be held liable for their improper behavior—and that any misconduct that occurred resulted from the decision of “State Prosecutor” Mike Nifong.

[An aside: With this wording, which appears throughout the brief, the Durham attorneys invent a new position in Durham County, whose voters apparently elect not a district attorney but something called a “State Prosecutor.” The reason for the sleight-of-hand is obvious—to downplay the actions of Nifong as head of the police investigation, actions for which he (and the police officers with whom he collaborated) are unequivocally liable; and instead to repeatedly label him an employee of the state, which has immunity under the 11th amendment.]

For instance, Durham wishes away the Gottlieb/Himan role in the meeting with Nifong and ex-lab director Brian Meehan, since neither “of the City investigators knew anything at all about DNA testing, let alone the industry customs and standards regarding the proper reporting format of such results. Indeed, Plaintiffs’ allegations make clear that State Prosecutor [sic: District Attorney, or at this stage of the case, lead police investigator] Nifong—not the City investigators—decided not only who would test the DNA, but how those results would be explained to the public, shared with the defense, brought before the grand jury, and presented to the Court.”

The falsely accused players’ attorneys dismiss this argument out of hand, given that “the detectives did not need to be experts in DNA testing to understand the simple conclusion that Plaintiffs’ DNA did not match that found on the rape kit items and, thus, that Plaintiffs could not have raped Mangum in the manner she claimed—a conclusion they already had reached in their investigation.”

Similarly, Durham cites Himan’s admission to Gottlieb and Nifong that no evidence existed to indict Reade Seligmann (“with what?”) to suggest that their officer corps acted without malice. Yet, as the players’ attorneys point out, this isn’t the message the DPD communicated with the grand jury, and so “the fact that the detectives and Nifong were candid with one another about the lack of inculpatory evidence and abundant evidence of innocence does not negate the allegations of malice when each of them took actions to conceal this fact from others.”

And in a line that would draw laughs from anyone remotely associated with the case, Durham concludes that Gottlieb’s myriad instances of misconduct resulted not from his (documented) malice toward Duke students, but instead was “explained by the seriousness of Mangum’s claim.” (This is about the only time at any point in the case that I have encountered an implication of ex-Sgt. Gottlieb as overly conscientious.) Countered the players’ brief, “Even if . . . Gottlieb thought that Mangum was credible and actually believed that she was raped, that still would not justify his actions in ignoring evidence of Plaintiffs’ innocence and trying to frame them for the alleged crime.”

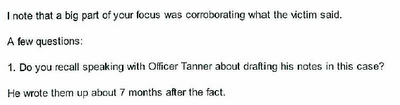

In fact, it seemed at times as if the Durham attorneys shared with their star client a tendency to mislead by omission. The players’ brief caustically observed that “nowhere in their entire brief do the City Defendants mention Gottlieb’s ‘supplemental case notes,’ which Gottlieb fabricated months after the indictments in an attempt to cover up inconsistencies and contradictions in Mangum’s actual statements regarding the incident. Such actions are hardly consistent with the claim that the detectives were simply making a ‘good-faith effort to investigate an allegation of a serious crime,’” as the Durham deems Gottlieb’s (mis)conduct.

According to the Durham standard, it seems, as long as the police deal with a “serious” claim of wrongdoing, they can behave according to virtually any standard. This line of argument is bizarre.

The city’s defense of Cpl. Addison for his parade of false, yet wildly inflammatory, statements against the lacrosse players is even stranger. The Durham brief suggests that as Addison did not participate in the actual investigation, the players can’t show that he knew his statements were false. And if he didn’t know his statements were false, he can’t be held to have acted with malice. This claim, alas, seems to prove the falsely accused players’ case, for if Addison knew nothing about the case, then he “had absolutely no basis for his false media statements that Mangum was ‘brutally raped’ at the party, that the players living at the house (one of whom was [David] Evans) had refused to cooperate with the search warrant, that there was ‘really, really strong physical evidence’ of a crime, and that some or all of the players knew about the attack and were obstructing the investigation, let alone for his ‘Wanted’ poster stating that Mangum was ‘sodomized, raped, assaulted and robbed’ in a ‘horrific crime’ during the team’s party.”

Contradictory Claims

The Durham brief manages to term exculpatory evidence as somehow supportive of a crime. For instance, the brief notes that “the following day, complaining of pain, Mangum told medical personnel at UNC Hospital that she had been attacked the prior day.” The brief doesn’t indicate where this “pain” allegedly was (Mangum’s back), nor that she hadn’t indicated any pain in the back the previous evening, nor that her goal appeared to be to get access to more prescription pain medication, nor that this follow-up trip to a different hospital (where she told yet another different story) would have seemed to a reasonable observer more evidence of Mangum’s mental instability. (The false accuser, by the way, is now facing a mental competency hearing in her murder trial, and the H-S implies that she’s been transferred to a state mental institution.)

And here’s how the Durham brief describes Mangum’s initial interaction with Gottlieb & Himan: “Repeating her earlier allegations, [emphasis added] Mangum told the officers that three men had raped her, and provided physical descriptions.” Mangum, of course, didn’t repeat her “earlier allegations,” since before (or after) March 16, 2006, she never offered a consistent version of events. And the Durham brief doesn’t mention that at least one of her “physical descriptions” from the March 16 meeting didn’t match any player on the lacrosse team, while those descriptions also didn’t even remotely resemble at least two of the people ultimately charged.

Durham’s Alleged Invulnerability

The Durham brief repeats the same argument already rejected by Judge Beaty—namely, that the city has no legal liability because the grand jury indictment “broke any causative link between the City Defendants’ investigative actions and Plaintiffs’ post-indictment arrests.” Indeed, Durham fumed, “the district court never considered” the issue. The players’ attorneys coolly replied that Beaty’s “opinion below devoted five pages to this issue and rejected the City Defendants’ argument because they are alleged to have misled the grand juries.” For nearly half-a-million dollars, you’d think Durham could get more thorough litigators.

In a troubling concession for Durham justice, the city’s attorneys also maintain that it doesn’t matter if Gottlieb and/or Himan lied to the grand jury (as Gottlieb, by his own admission, did): neither they nor the city can be held liable for their behavior.

In their reply, lawyers for the falsely accused players gently observe (quoting from multiple cases) that “case law establishes . . . that the chain of causation is not broken, and a police officer is not relieved of liability, where—as here—the officer is alleged to have ‘misrepresented, withheld, or falsified evidence’ that influenced the grand jury’s, or another independent decision-maker’s, decision to indict or bring charges. In such a case, a ‘prosecutor’s decision to charge, a grand jury’s decision to indict, a prosecutor’s decision not to drop charges but to proceed to trial—none of these decisions will shield a police officer who deliberately supplied misleading information that influenced the decision.’”

Intriguing Claims

(1) The Durham brief maintains that the city has immunity, “because its insurance policies [which, if they exist, would mean that the city waived immunity] do not cover the conduct alleged here.” Yet, the lacrosse players’ attorneys “have identified numerous contradictory statements by the City regarding its insurance coverage, which demonstrate not only that the City does appear to have such coverage, but that summary judgment cannot be granted on this issue prior to discovery.”

(2) The Durham brief also claims that Gottlieb and Himan can’t be held liable for conspiring to produce a false DNA report, since “the DNA report was compiled after Plaintiffs Seligmann and Finnerty had already been indicted—so it could have had no effect on those indictments.” Of course, the duo’s initial meeting with Nifong and Dr. Meehan—in which, by the accounts of Gottlieb, Meehan, and Nifong, they discussed the DNA evidence that would appear in the report—occurred before any indictments, on April 10, 2006.

(3) The Durham brief includes this curious clause: “Corporal Addison is alleged to have made certain statements between March 24 and March 28 as the ‘Durham police spokesperson.’” Are the Durham attorneys suggesting that Addison didn’t, in fact, make the statements? That he lied when he identified himself to reporters as the acting department spokesperson? That he made some statements but not others? Who knows—the brief never says.

In any event, Durham concludes that “a reasonable officer [would] believe, at the time of Addison’s statements . . . , that [he was] not violating any constitutional right.” (Durham’s new motto: Durham, Where Police Officers’ Slander Doesn’t Violate Any Constitutional Right.”) Judge Beaty’s ruling disagreed, noting that “a reasonable official would have known that it violated clearly established constitutional rights to deliberately make false public statements regarding a citizen in connection with an unlawful arrest of that citizen.”

(4) The Durham brief admits that the April 4 photo array was “suggestive,” but contends there was nothing wrong legally with Gottlieb and Nifong conspiring to run a photo ID outside Durham’s procedures, without any fillers, and after Mangum had already failed to identify two of the people ultimately charged. Indeed, the brief breezily continues, “No reasonable police officer would know that . . . arranging a suggestive photo array violated a constitutional right if the resulting identification was not entered into evidence at trial.” In other words: in Durham, it’s OK to arrest people on rigged ID’s, and then simply not produce the evidence of the riggings at trial. And even more chillingly, Durham maintains that “Plaintiffs’ right [and, by inference, the right of all Durham citizens] to be free from ‘malicious prosecution’ is thus hardly ‘beyond debate.’”

This assertion drew a stinging reply from the players’ attorneys. Quoting Beaty’s ruling , they noted that “’there is no question’ that the right not to have ‘government officials deliberately fabricate evidence and use that evidence against a citizen’ was ‘clearly established’ in 2006. For good measure, the players’ brief quotes a 1st Circuit case, Limone v. Condon, which observed, “Although constitutional interpretation occasionally can prove recondite, some truths are self-evident. This is one such: if any concept is fundamental to our American system of justice, it is that those charged with upholding the law are prohibited from deliberately fabricating evidence and framing individuals for crimes they did not commit.” That Durham appears to believe otherwise is remarkable.

(5) And finally, in an attempt to get police supervisors and former City Manager Patrick Baker off the hook, the Durham brief offers the following howler, regarding a late March 2006 meeting between Baker, ex-Police Chief Steven Chalmers, and the police investigators: “even if Baker and Chalmers ‘ordered’ the investigators to ‘expedite’ the case, the much more likely ‘obvious alternative explanation’ is that they were attempting to bring the case to closure, rather than to convict innocent people.” So that’s what was going on—it’s more likely than not that Baker and Chalmers were pressuring Gottlieb and Himan to close the case and ensure that no criminal charges were filed.

Nothing in the exchange between attorneys for Durham and the falsely accused players changes the basic conclusion from Beaty’s March ruling: "Defendants in this case essentially contend that this Court should take the most restrictive view of the applicable doctrines and should conclude that no provision of the Constitution has been violated, and that no redressable claim can be stated, when government officials intentionally fabricate evidence to frame innocent citizens, even if the evidence is used to indict and arrest those citizens without probable cause. This Court cannot take such a restrictive view of the protections afforded by the Constitution."