Cohen had a far different take, however, on the lacrosse case, writing in June 2006 that discussion about Mike Nifong's procedural misconduct meant that, in the media, “there is no balanced coverage in the Duke case. There is just one defense-themed story after another.” The lacrosse players, he claimed in apparent ignorance of the first month of the case, benefited from “race and money and access to the media.” And when the victims of a rush to judgment were college students rather than the former IMF head, Cohen's interpretation of legal ethics went as follows: “We haven’t seen all of the evidence, haven’t examined all of the testimony; haven’t had the privilege of seeing the case unfold at trial the way it is supposed to.”]

As I’ve noted previously, there were significant differences between the lacrosse case and the allegations against French politician Dominique Straus-Kahn: in the DSK case some type of sexual contact occurred; and even his version of events reflected poorly on the former IMF head's character.

It turned out, however, that the most significant difference between the two cases involved the office of district attorney. With the exception of an ill-timed public statement early in the case, Manhattan DA Cyrus Vance, Jr., followed both ethical guidelines and normal investigative procedures. Mike Nifong, of course, did not. A few items from the dismissal motion filed by Vance’s office:

Prosecutor’s Duty

Vance's office spelled it out in the dismissal motion:

Nifong, by contrast, spoke of false accuser Crystal Mangum as “my victim,” and as late as Dec. 2006 ignored basic ethics and described his role as purely a gatekeeper: “If she says, yes, it’s them, or one or two of them, I have an obligation to put that to a jury.” These comments came several weeks after what was perhaps his most chilling remark of the entire case, when he claimed that not the evidence nor even his beliefs but instead divisions within the community sufficed as a cause to bring the case to trial.

Continuing the Investigation

Consider these passages from the motion, describing the Manhattan DA office’s continuing investigation:

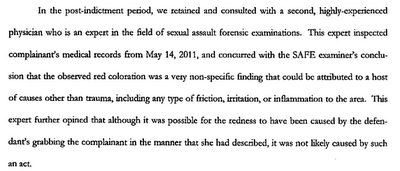

This investigation included a critical analysis of the medical evidence:

Nifong, by contrast, preferred willful ignorance; he claimed that, until his case imploded with the Dec. 2006 Meehan hearing, neither he nor anyone from his office asked Mangum anything about the case. And neither he nor his office appear to have challenged the ever-changing testimony of former SANE-in-training Tara Levicy.

If Vance and Nifong differed, some elements of the political and intellectual community evident in Durham carried over into New York.

Sunday's New York Times reported that "Bill Perkins, a state senator from Harlem, who like Mr. Vance, is a Democrat, stood alongside black and female leaders and urged Mr. Vance to press forward with the case . . . Mr. Perkins and others framed the case as a possible instance of a powerful white man getting off for something he did to a poor immigrant woman. . . . Councilwoman [Letitia] James said that if the case was dismissed over credibility issues,'it would have a chilling effect on all rape victims, and it would send a message to all rape victims that unless you are a perfect rape victim, you should not even bother to come forward.'"

There’s little reason to believe that James or Perkins will suffer any political repercussions for their indifference to due process; but if they do, they could discuss survival strategies with one of the most vociferous apologists for the DPD’s procedural shenanigans, City Councilor Diane Catotti, who remains in office, and seems likely to win re-election this fall.

Alas, the Durham Democrats have removed from their website the 2006 photograph of a beaming Catotti standing by her endorsed candidate for her city’s minister of justice, Mike Nifong. But even without the photo, based on her record in the lacrosse case, those who presume guilt in sexual assault cases and are indifferent to procedural misconduct by authorities have no better friend than Catotti.